Can We Learn To Understand Our Society by Studying Ancient Religious Sites in Their Natural and Social Context?

Our perception of Earth can be quite superficial. We are able to live on Earth only because it is in an exact place in the solar system, but we never sit down to think about this or how it all works.

Similarly, when we think about religious places, like churches, mosques, or ancient temples, we might associate them with a specific community, beliefs, and religious customs, appreciate their architecture or consider if they are in the city. However, we do not stress enough the importance of their location and the external elements and factors around them which make a religious place.

My project offers an insight into how society works and hopes to make people more aware of where they live. It focuses on how various elements and factors are interacting and shaping our territory and how the location of different elements that surround us (type of terrain, cities, roads) can also be determinant factors in forming the place where we live. In our everyday life, we pay very little attention to all these factors and our surroundings.

In my WiRe research project – but this is true for any archaeological projects – we want to understand how different pieces of a puzzle are put together. The puzzle in question is past societies and it can be potentially applied to our society. Before jumping right into the project, let’s get the basics right!

What is archaeology? What does an archaeologist actually do?

Archaeology is definitely not the job of Ross from Friends! He was a paleontologist who dug up dinosaurs! Archaeology also does not involve chasing bad guys who want to steal artefacts, like the long-lost Ark of the Covenant, as Indiana Jones did. Nor do archaeologists race against time and villains to recover powerful ancient artifacts while wearing a tied outfit like Lara Croft.

Although TV shows, computer games and movies make archaeology more visible to the public, the examples mentioned above are fictional characters. Archaeologists excavate remains of people from the past, from houses to tombs, including temples or rubbish pits. Archaeologists do not just dig; they spend a lot of time doing research in libraries, collecting data from catalogues or articles, putting them together, making sense to them and interpreting them to reconstruct a narrative of past societies. In addition, we archaeologists often collaborate with different experts to discuss data, our results and often exchange ideas through online meetings or during conferences (Check out my interview for an insight into my typical day!). When we can, we visit sites that we are working on, if we do not run excavations or surveys.

Now that we have a clearer idea of what archaeologists like me do, let’s get into my research project!

What is an (ancient) religious site? What is Garvão?

Public religious sites in ancient times vary widely in form and function. An ancient public religious site can manifest as a monumental building like a Greek or Roman temple with a colonnade housing the statue of a god inside the building. Sometimes, only inscriptions or the statues of gods remain, offering glimpses into the site’s religious significance. Alternatively, a religious site can be a deposit carrying a profound religious meaning. Such significance can be attributed to the location, like the foundation of a temple, or more commonly, the types of materials that have been deposited. These materials might include religious figurines or an unusually large quantity of materials, like ceramics recovered in a large pit.

For my project I am not considering fancy monumental religious public buildings. Instead, I am looking at a big oval deposit measuring 10 by 5 metres and one metre deep located in Garvão, southern Portugal.

This deposit, dating back to the Iron Age (third century BC), comprises various layers of similar pottery stacked together. The stacks start with bigger vessels at the bottom and continue with dishes and smaller vessels at the top. Hand and wheel-made decorated drinking vessels, cups, and fewer jugs were found. The ceramics recovered were storage pottery and mainly tableware used for religious banquets and rituals. Even most of the containers were decorated, suggesting that they had been displayed and not just used for storage. In addition, 140 incense burners and an aspergillus were found within; the former could have been used to burn incense as part of rituals and the latter was perhaps used to sprinkle water for ritual activities. The deposit also includes loom weights, female and animal figurines, female figures on some vessels, as well as gold and silver plaques adorned with depictions of eyes. This set of objects suggests the worship of a fertility female god standing for the local god of the place.

Most notably, at the bottom of the deposit, a 35-40 years old woman’s cranium featuring signs of injury was recovered in a stone box, accompanied by scattered animal bones. The animal bones could be evidence of feasting and sacrifice associated with the deposition of this skull. Apart from the wealth and large quantity of finds in the deposit, their nature clearly suggests that the deposit was of religious significance. It could have been a votive deposit of large numbers of sacred utensils and votive objects no longer in use. These objects may have been votive offerings to a god with their deposition intended to gain favour with supernatural forces, in this case of a local god with a female appearance. The deposit, often referred to as favissa, may also have served as a storage space for these cultic objects.

My project “Garvão into context”: A multileveled approach

My project “Garvão, a Sacred Place into Context” investigates the location and socio-economic context of the votive deposit described before at Garvão in southern Alentejo, Portugal.

In practical terms, the questions that my project is putting forward are:

- Was the religious site on a road?

- Was it in a city or near a settlement?

- Was it on the top of the mountain or near fresh water?

These questions can make us think about accessibility, visibility, sustainability, and the sacredness of natural elements, for instance.

Ancient sites are often situated near water for sustainability because of the easy access to fresh water for daily use and economic purposes. However, water was also considered sacred due to its healing properties and was used for ritual activities. Temples were situated near water sources and people used to throw votive offerings into rivers, lakes and water springs. The Roman temple dedicated to Minerva Sulis was near the water spring in Bath, England, where offerings and cursing tablets were thrown into the water. A similar sanctuary that involves rituals of throwing votive offerings into the water spring is the Etruscan and Roman sanctuary located at San Casciano dei Bagni in Italy, where excavations are ongoing. However, Iron Age settlements were also often on top of a hill for protection and visibility, like the near site Castro da Cola in southern Alentejo. Religious sites were also sometimes positioned atop hills to ensure visibility to pilgrims and/or to the local community, as well as to create a closer connection to the gods.

Could the streams suggest and stress the importance of the sacrality of the place?

The votive deposit in Garvão rests on the slope of a hill facing the Iron Age settlement. Situated at a river bifurcation, two river streams almost encircle both the votive deposit and the Iron Age settlement in Garvão. Could the streams suggest and stress the importance of the sacrality of the place? The remnants of the settlement consist of slabs and ceramic finds below Islamic domestic ruins. The reuse of the settlement in the Islamic period makes it difficult to have a full understanding of the site in the Iron Age. In addition, it is difficult to fully understand the extent of the settlement and other possible religious structures associated with the votive deposit because they are at the edge of the modern-day village of Garvão. Was the Iron Age settlement in function of the religious site?

Ceramic sherds from the late Bronze Age were found below the voting deposit, suggesting a long-term occupation of the territory. The substantial amount of locally crafted pottery, like the incense burners and figurines, suggests that they could have been materials made for use as offerings for a major public religious site. The votive deposit is only a secondary deposition of the materials used in its surroundings. This type of materials was most likely used for ritual activities. They could have taken place on top of the hill. There, the visibility of the surroundings, apart from the nearby settlement, is even greater than that from the votive deposit. At the top of the hill only Islamic structures have been recorded so far. However, thick layers of alluvial soil above the votive deposit are rich of sparse materials from different types of periods, including the Iron Age and the Roman period. They have probably come from the top of the hill, suggesting long-term occupation even before the Islamic period.

The link between the settlement and the deposit is confirmed by similar pottery found in both contexts. Garvão was connected to other major Iron Age settlements through ancient pathways which could suggest that this religious site has been used by the wider community and that there was no other site with a religious significance in its surroundings. The presence of loom weights, along with animal figurines, can be considered as a reflection of the local economy of that time, predominantly based on husbandry and textile production. This set of objects together with female figurines and their representations on vessels jointly deposited can indicate a link between the worship of a local female fertility god and items that were daily used by the community and symbolising their economy. In addition, the depiction of eyes on gold and plaque in the deposit can suggest that Garvão was a place for healing and protection.

Was it, perhaps, because of the sacredness of the place – being on the hill or near the water streams – or is it just indication of the worship of local gods? Examining the religious site within its context helps to reconstruct what happened in the past. However, at the same time, it also raises still open-ended questions. Further on-site examination may help to provide a deeper insight into some of these questions and answer some of them. This constitutes the plan for the next phase of investigation of the site and its surrounding territory.

Can archaeology help us in understanding current issues and our present societies?

It is not a novelty to use archaeology to understand the present. A lot of interesting and exciting work has been undertaken on contemporary issues such as climate change, just to name one example.

One notable project is the Climate, Landscape, Settlement and Society: Exploring Human-Environment Interaction in the Ancient Near East project which aims to collect archaeological settlement and archaeobotanical (plant and tree remains) data for the entire Fertile Crescent region. This archaeological research can help us in understanding abrupt and longer-term climate changes, utilizing the ancient Near East as a case study. In contrast, projects like CITiZAN, the Coastal and Intertidal Zone Archaeological Network exemplify community-led efforts that address climate change, particularly focusing on empowering members of the public to safeguard England’s vulnerable coastal archaeology. Similarly, the Medieval Climate Change Project explores how people responded to environmental and climatic change during the medieval period.

On a smaller scale, my previous Marie-Sklodowska-Curie-IF-project investigated the importance of interactions between people and their movement in shaping religious traditions, and ultimately culture and societies, in the Roman period. The project can shed some light onto the cultural plurality and diversity of past societies as the result of migration. It is an important topic in a time of nationalistic movements and migration restrictions. A previous WiRe project undertaken by Aleksandra Kubiak in 2020 also covered multiculturality and religious tolerance. As she explains, the lack of this consciousness leads to the destruction of ancient monuments like those in Syria . Ultimately, the role of archaeology in our society is to educate people and to makes stories from the past available to the public that can help us to understand and live in the present.

What message can be taken away from my current WiRe research project?

Three key ideas I aim for readers to take away are: firstly, the importance of examining archaeological sites on multiple levels and collaborating with scholars to gain a deeper understanding of the past. Secondly, by examining the votive deposit of Garvão within its context, individuals can reconnect with their surroundings and recognize their integral role in shaping their environment. Lastly, studying the past provides valuable insights into the present, while simultaneously allowing us to use contemporary knowledge to interpret fragmentary evidence from history. This study encourages people to reconsider the significance of learning about the past to better understand and navigate the present world.

Behind the Scenes: Collaborations & Workshops around my WiRe Research Project

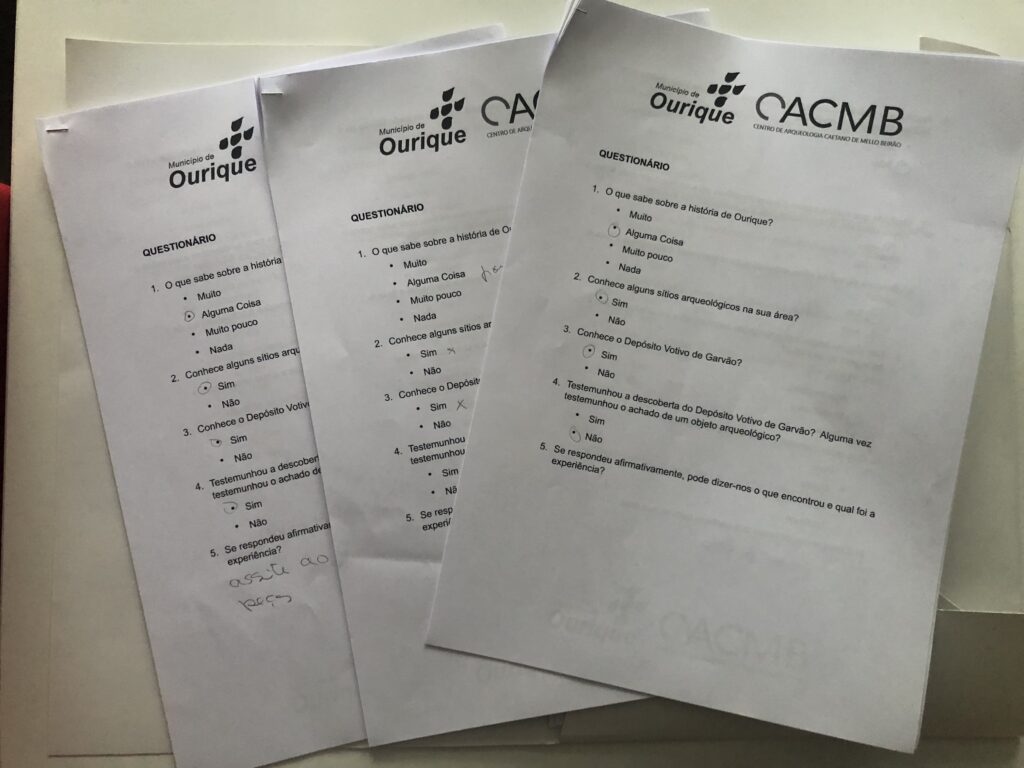

For this WiRe research project, I closely collaborate with my Portuguese colleague, Tiago Costa, through online meetings and during my stays in Portugal. During these visits, I conduct site visits, examine artefacts, meet with local political authorities, planned our joint paper and future collaborations for further investigation of the sites and its surroundings through fieldwork. Also, we organized a workshop with the local community of Garvão to learn about their experiences with previous archaeological excavations, communicate with them about our project, and discuss their potential involvement in future work on their territory. This engagement serves as a means to empower them and preserve their heritage.

While the WiRe fellowship has generously funded my individual work on the project, a key component is also my collaboration with colleagues from Münster and from Portugal. My stay in Münster has helped me to think differently and broaden my horizons through the mentorship of Professor Dr Achim Lichtenberger, colleagues from the Department of Classical Archaeology and Christianity, and my participation in the Interdisciplinary Research Cloud Religious Landscapes and Environmental Devotion at the University of Münster.

This collaboration has led to the international workshop “Belonging and Sacred Places in Antiquity” in Münster on December 11-12th 2023 that I co-organised with Professor Dr Achim Lichtenberger, Dr Sophia Nomicos and Dr Marian Helm to discuss the importance of natural landscapes and the environment. The workshop was generously funded by Cluster of Excellence Religion und Politik at the University of Münster.

The workshop enabled us to bring together colleagues from Brazil and Portugal to discuss sacred places with German and European colleagues and to also spread awareness about the archaeology of Portugal which is not a popular geographical area of investigation in Münster or in Germany. It will lead to an edited volume with most of the papers presented at the workshop and I will edit the volume with Professor Dr Achim Lichtenberger, Dr Sophia Nomicos and Dr Marian Helm. In this volume, I will also present the results of my project associated with the theme of belonging in a separate chapter.

If you want to always be kept up to date, check out Francesca’s LinkedIn account, her personal and the project‘s old X account as well as her publications.