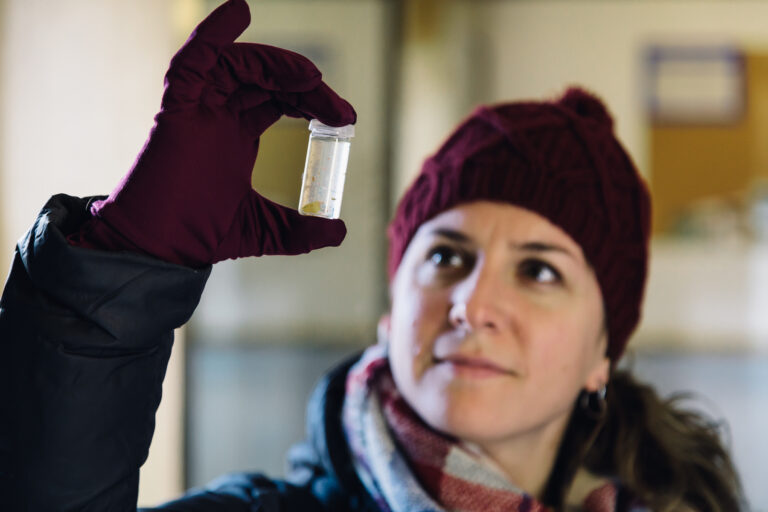

Asking the Biggest Questions With Theologian Dr. Julija Naett Vidovc

In the series “33 questions” we introduce, in no particular order, our WiRe Fellows who are currently working on a research project here at the University of Münster. Why 33? Well, if we think of the rush hour of life, it is kind of the age that lies in its middle. And we also like the number😉.

In today’s episode we are speaking with Julija, theologian and passionate lover of Christian anthropology.

1. What motivated you to work in the field of Christian anthropology?

Ever since I was a child, I have been fascinated by existential questions: What is life? How do people understand death? What exactly entails the ‘good life’? … and so on. What is fascinating about these questions is that the more we dig into them, the more they dig back into us by multiplying and becoming more complex. It’s a never-ending adventure.

2. Describe your daily work in three words.

Breathing, listening, writing.

3. Describe your research topic in three words.

Humanism, transhumanism, Christ.

4. A good theologian needs…?

Prayer.

5. What is the best experience you have had as a scientist / researcher?

Having to return to my original considerations and assumptions in order to correct them.

6. What was your biggest research disaster?

My first post-doctoral research project was not successful. At that time, it was devastating because I really needed to follow through on that commitment. Looking back, I see that it was not so much a disaster as I thought, and that allowed me to move forward. However, at that time I did not take it well.

7. Which (historical) important scientist would you like to have dinner with? What would you ask?

There are several, but if I have to choose one, I’ll say Origen, so that he can explain to me his understanding of the concept of Apocatastasis (the salvation of all).

8. If time and money were no object: Which research project would you like to do?

The same one I’m doing right now.

9. What is your favorite research discipline other than your own?

Quantum mechanics.

10. What do you consider the greatest achievement in the history of science / your field?

There are several, but I will put forward the Christian concept of the human person. The contribution of the Greek Church Fathers in this field is enormous, but in recent years it has been reformulated and propelled by philosophers and theologians, such as Nicholas Berdiaeff, George Florovsky, and John Zizioulas.

11. Which experience in the world of science disappointed you most?

CRISPR babies – mutations produced with the use of CRISPR-Cas9 tool into human embryos, which were then used to produce babies.

12. What was the funniest moment you had in science?

Due to an organisational mix-up at a large conference involving a multitude of speakers, I ended up speaking on my topic of the transhumanist understanding of man to many nurses. There was total confusion on both sides. It was impossible to change the situation at the last moment, so we tried to play along and all pretended to mutually follow and understand the issues from both sides.

13. How did you survive your PhD time?

At first it was very difficult. I really liked the field of research I was going to do and the research itself, but unlike my colleagues, especially those who were close to me, I had no clear career plan. Most of them knew which position and where they were going to work once they had obtained their PhD, whereas I had no idea and felt like I was going down a path that would take me nowhere. As my research progressed, these questions gradually dissolved and the research itself became my career path.

When one works in the field of scientific research in physics, biochemistry, medicine, etc., one can dream of changing the world by discovering innovations that will profoundly transform the conditions of human life, which can also be the case for research in the field of the sciences of interpretation (economics, sociology, psychology, law, etc.). In theology on the other hand, it is only a matter of serving the Church’s continuing fidelity to the Gospel, its fidelity to a truth that precedes it. The responsibility of theology thus appears less as a responsibility of foundation than of rectification. In fact, theology does not invent what founds it, nor does it have to do so. It finds its foundation where it is given: in the Christian tradition as a tradition of community life within which the believer relates in thanksgiving to his Creator according to the incarnation and the paschal mystery.

On the other hand, it is up to theologians to constantly rectify the way in which believers relate to this foundation. Having said that, what interests me in this particular research is the additional consideration of the anthropological crisis that affects us all, wherever we come from: no continent and no country can escape it. It therefore requires an examination not only of the resistance to the deconstruction of the human, but also of some typical situations of today’s society, generally denounced as signs of its dehumanisation, which reveal ways to rebuild a humanism and a positive ethic marked by the seal of fragility.

14. How did you imagine the life of a scientist / researcher when you were a high school student?

A great and luminous adventure of spirit; like a search for hidden treasure.

15. Is it actually different? In what way?

It’s still the same, but much more concrete and involving others – family, friends, colleagues who sometimes don’t want to play along on this treasure hunt.

16. What do you like most about the “lifestyle” of a scientist? And what least of it?

Most: being able to spend the day reading without having to justify it. Least: not having enough time for loved ones. And of course, figuring out how to make do with rather limited income.

17. Do you think your career would have evolved differently if you were a man?

Probably. But I can’t say whether it would be for the better or not.

18. If you were the research minister of Germany, what would you do to improve the situation of women in science?

I would attempt to propose innovative hiring criteria that take into account the unique life experiences of women: family responsibilities, and women’s sensitivities related to their direct contact with life (giving birth to children, caring for the elderly or vulnerable, etc.).

19. If you had a daughter, what would you advise her not to do?

To not be envious of anyone.

20. How would you explain your research area and topic to a child ?

I still remember when I was around 5-6 years old wondering how it would be possible that the carousels will continue to turn, but that we will no longer be around. In fact, at that time my great-grandmother had just died and I was told that she no longer exists – like a dry leaf that withers away.

So, in this sense, I would say to this child: the carousels continue to turn, and so do we. After our earthly disappearance, we will continue to play in a place which we cannot see clearly right now, even though we can feel it. The problem comes when we don’t want to accept the movement to that place; when we are afraid to make that transition. Out of fear, we try to invent ways to stay here indefinitely in this world, and this is the source of many problems. This world then becomes a form of prison and loses its allure of the playground. Ultimately, it seems to me that children understand these questions better than we do.

21. What is the biggest challenge for you when it comes to balancing family and career?

Clearly defining the times for both. I either lack the time and energy for one, or for the other.

22. How do you master this / these challenge(s)?

I have not mastered them, but if I manage to do so, I will let you know.

23. How often do you as a friend / partner / mother / daughter feel guilty when you have to meet a deadline – again?

Often. And I keep saying that this is for the last time.

24. How did you imagine your future as a child? What profession did you want to pursue?

I didn’t think of the world in terms of a profession. I always saw myself as helping those in need. However, having once watched from afar a big forest fire on an island, for a long time I wanted to become a fireman to save the animals because I was unable to imagine how they would manage to get away from it.

25. What is your favorite German word?

Frühstück.

26. What makes you most happy about the world?

Children.

27. What or who inspired you to become a theologian?

The Holy Scripture.

28. What worries you most about the world?

The lack of imagination. Evil is always identical to itself, while goodness is always different and varied, for it is always genuine.

29. Your favourite TV series?

I avoid watching TV series, as I can’t stop once I start watching them.

30. If someone asks you about your age, what do you respond spontaneously?

I’m joking with my nephews that I still have two years. So, every birthday they ask me if I’m going to be three and I tell them proudly that I’m not. Otherwise, I feel good about my age.

31. If you could travel in time: in which epoch and at which discovery or event would you have liked to have been there?

I will say during the time of the earthly life of Jesus Christ.

32. What are the advantages and disadvantages of doing a Research@home-WiRe-fellowship?

Being able to stay at home with my loved ones is certainly an advantage. Not being able to go to libraries, meet other researchers and share with colleagues spontaneously poses a bit of a challenge at times.

33. What is your favourite place to relax from research during the pandemic?

Cycling in my neighborhood while listening to music.