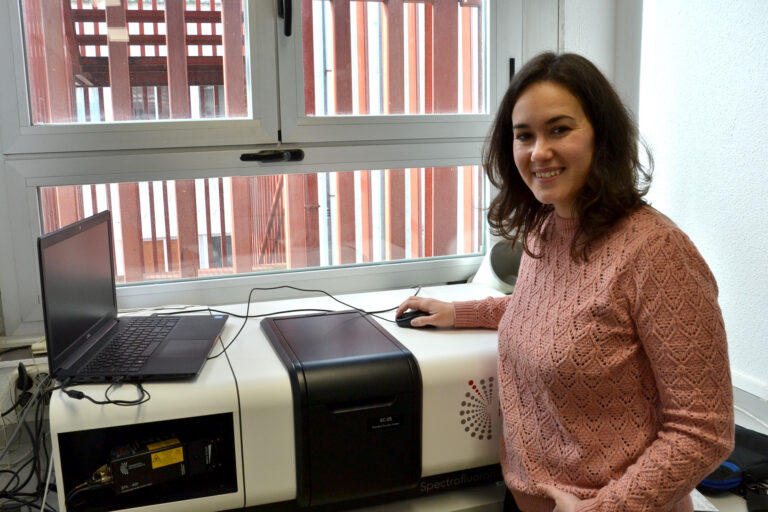

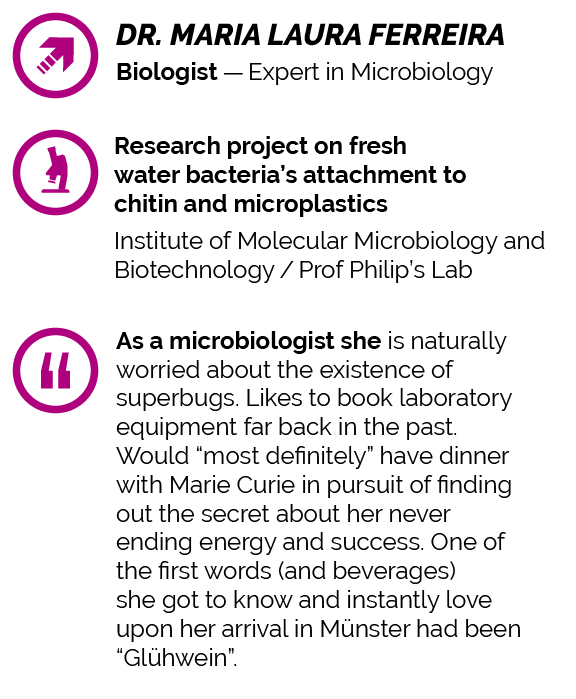

Chemist, Biologist, Environmental Scientist – the Many Roles of Dr. Maria Laura Ferreira

In the series “33 questions” we introduce, in no particular order, our WiRe Fellows who are currently working on a research project here at the University of Münster. Why 33? Well, if we think of the rush hour of life, it is kind of the age that lies in its middle. And we also like the number😉.

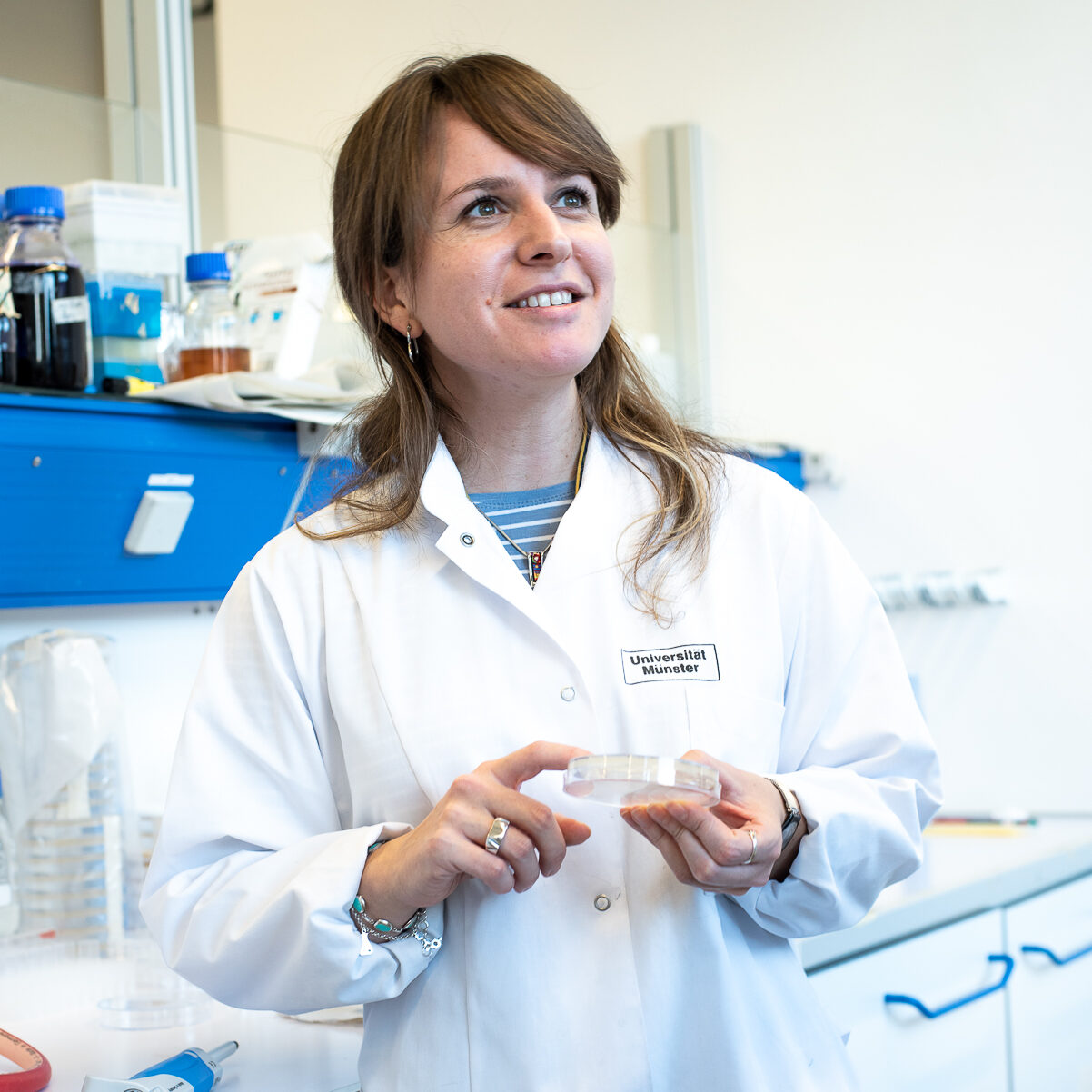

In our first-ever episode we are speaking with Dr. Maria Laura Ferreira, a passionate microbiologist dedicated to fighting environmental pollution.

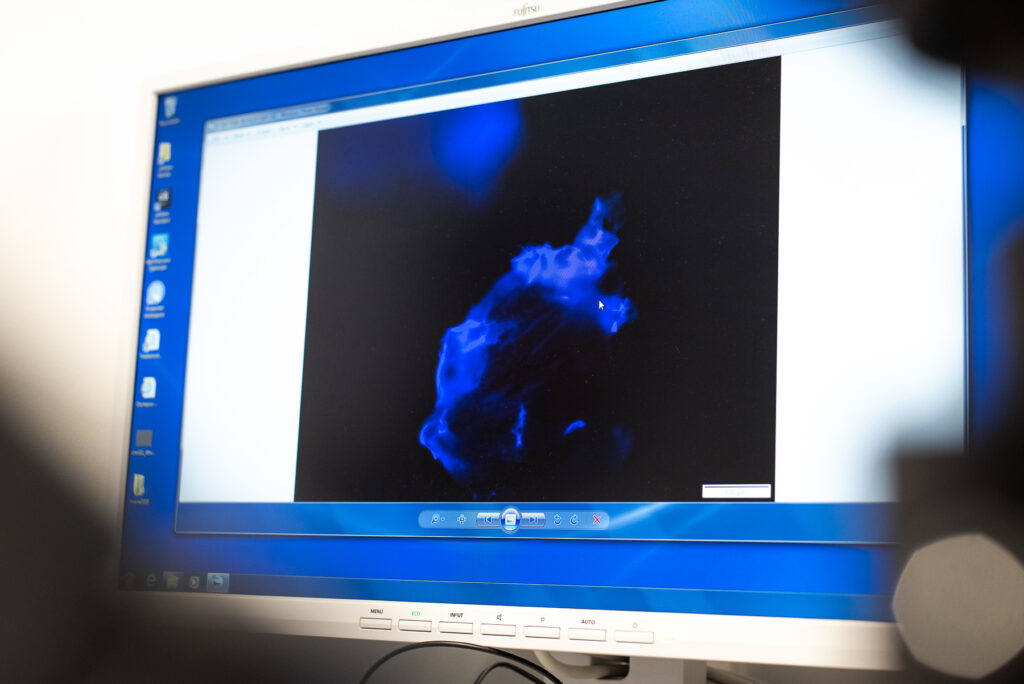

Since her WiRe Fellowship, Dr. Ferreira has also contributed as a guest blogger! Read more here to learn a bit about a bacteria which eats microplastics.

1. What motivated you to work in the field of microbiology?

My dream has always been to become an environmental scientist and work to protect the environment, helping to mitigate anthropogenic pollution. While still in high school, I discovered that I was also passionate about chemistry, which led me to pursue a graduate degree in that field. Microbiology seemed like the perfect arena to use my passion for chemistry in developing solutions to address some of the most pressing current environmental issues.

2. Describe your daily work in three words.

Planning. Patience. Analysis.

3. Describe your research topic in three words.

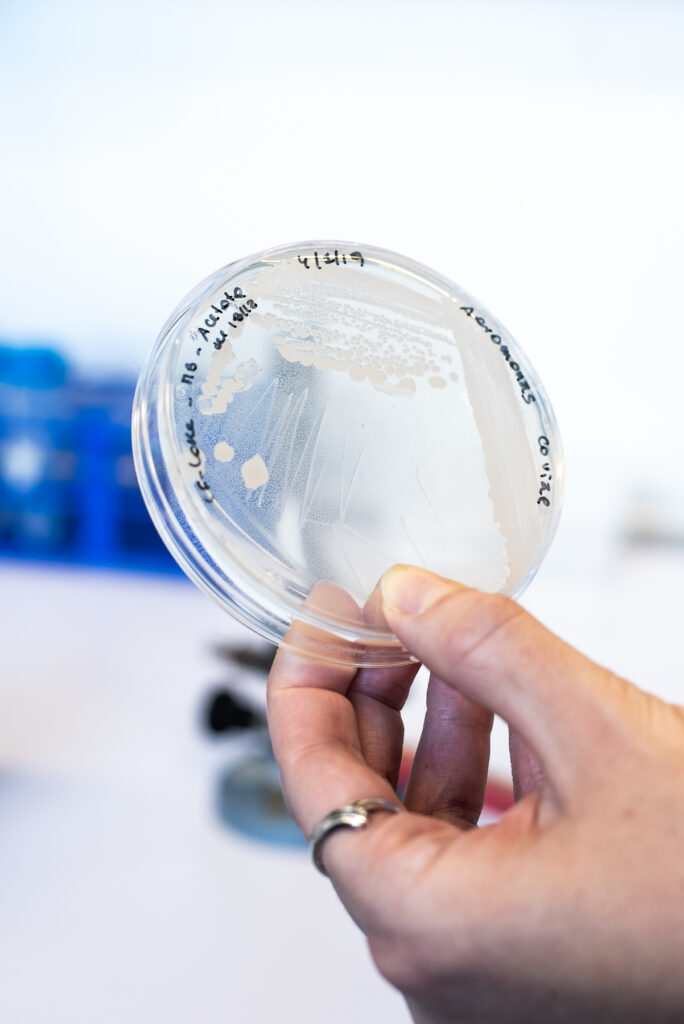

Bacteria. Aquatic. Pollution.

4. A good microbiologist needs…?

… to be passionate about chemistry and biology, because microorganisms are just little organisms where biochemical reactions are involved. In addition, it is necessary to have a curious mind, to think outside the box and to be able to ask many questions about how / what / why the observed processes are happening, and being able to come up with possible answers for all those questions. Additionally, as with any other good scientist, it is essential to work in pursuit of the common good, be responsible, and know how to work as a team.

5. What is the best experience you have had as a scientist?

For me, when I managed to describe a new microbiological process. Regarding microbiology and environment, I feel proud to contribute to the understanding of how bacteria could be used to bio-treat environmental pollution and how bacteria interact with anthropogenic pollutants. Most likely, I will not be awarded a Nobel Prize for that, but it is my sand grain contribution towards a better world. On the other hand, as a teacher and researcher, being able to contribute to developing the scientific curiosity in young students is truly rewarding.

6. What was your biggest research disaster?

When I was writing my doctoral thesis, the last (but not least!) point was to analyze chromatograms, the output of an analytic technique that contained critical information about the structure of the compounds I had been studying for the last 5 years. When I turned on the computer and looked for the files in the corresponding folder, I realized that the folder was empty… AND I DIDN’T HAVE A BACK-UP! Of course, the process of writing a PhD thesis was already driving me crazy, and in that moment I felt particularly dumb: How could it even be possible that I didn’t make a backup?! Luckily, my husband helped me calm down and figure out a solution. With a bit of luck on my side, I could get the files again after a few days and I was able to analyze them and round out my doctoral thesis.

7. Which (historical) important scientist would you like to have dinner with?

It would most definitely be Marie Skłodowska “Madame” Curie. She was one of the most inspiring women in science. Born in 1867, her birth country denied her a position at Kraków University on the basis of being a woman. However, such a setback did not stop her: she won two Nobel prizes (one in Chemistry, and another in Physics!), she was the first woman to become a professor at Sorbonne University, she made important humanitarian contributions during World War I, she was a mother, and she raised a daughter who also managed to win a Nobel Prize in Chemistry!

8. What would you ask her?

I’m thinking of a lot of questions, but some of them would be: How were you able to break the male-dominant paradigm and manage your position as a woman in science? What was the process of becoming the first female teacher like? How did you have enough leftover energy to raise your daughter on those tough times and encourage her to pursue a career in science, knowing how difficult that path had been for you?

9. If time and money were no object: Which research project would you like to do?

In many aspects, my home country Argentina is a land of contrasts. We have one of the biggest freshwater reservoirs in the world, but also one of the most polluted rivers in the world, and lack of access to drinkable water in some remote regions. There are different research groups in different institutions trying to tackle the problems with water pollution and scarcity, but they all work separately, and I feel that from time to time, they “reinvent the wheel”.

I would like to create a national programme integrated by members of all those research groups to share information and work together towards a unique and common solution; I think that would help us get much faster to an acceptable solution. In a way the MirkoPlaTaS project where I am working at the University of Münster with Professor Bodo Philipp and his team is a source of inspiration for that research project.

10. What is your favorite research discipline other than your own?

Well, to be honest, I am working in my favorite research discipline, which is different from my own ;-). As I mentioned earlier, I got my graduate degree in Chemistry, and one of the last subjects was Microbiology. I loved it! … Therefore, after obtaining my degree in chemistry, I applied for a fellowship to do my PhD in microbiology and was lucky enough to get it! I am continuously learning about this wonderful science field.

11. What do you consider the greatest achievement in the history of the science of microbiology?

I think the most remarkable achievements in the history of science that impacted our understanding and knowledge in the field of microbiology are:

- The discovery of the DNA Double-Helix structure

- The invention of the microscope

- The discovery of antibiotics

- The discovery of the pasteurization process

- The CRISPR-Cas discovery

12. Which experience in the world of science disappointed you most?

I believe that categorizing a researcher for the number of publications he / she produces is rather disappointing. I understand the game rules, but the hurry to publish or to have a growing number of publications can hinder the real goals.

13. What was the funniest moment you had in science?

I had a lot of funny moments in the laboratory. Some situations come to my mind: usually, if a scientist needs to use an equipment, she / he has to book it with the date and time she / he is planning to use it. More than one time I booked laboratory equipment far back in the past! So, my colleagues made graphic jokes about that (e.g. featuring my face in the movie back to the future) and would post them on the windows in our office, so the entire institute could see them.

14. How did you survive your PhD time?

The most important factor that helped me survive through that stressful time was that I was working in a nice and cheery laboratory. And of course, the endless support from my husband to cope with all the up and downs that a PhD student goes through.

15. What direct or indirect relevance does your research have for society?

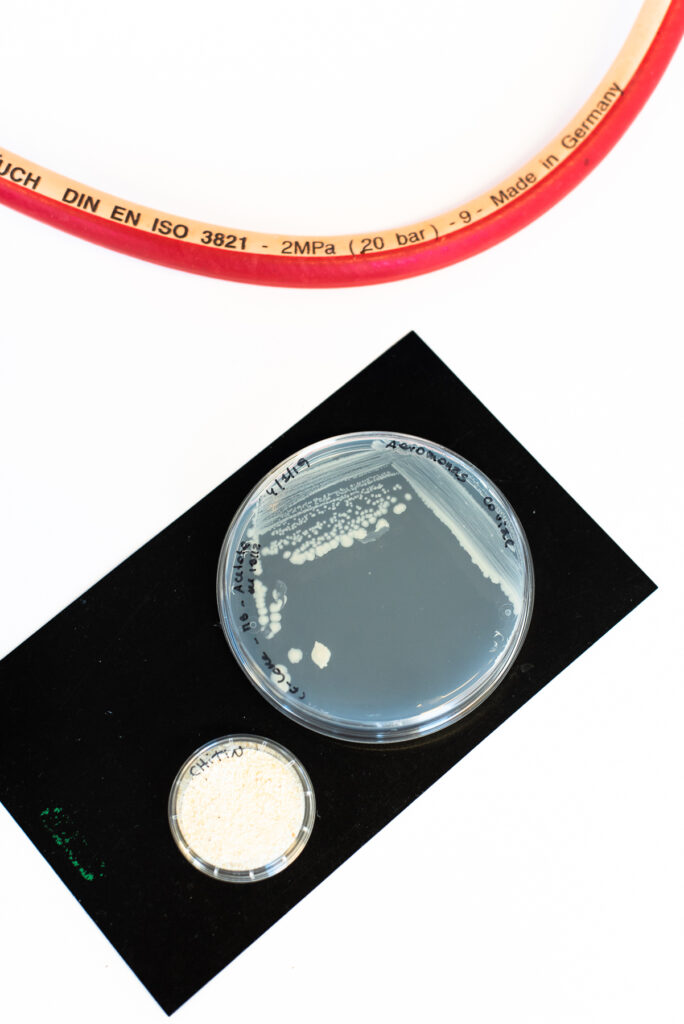

My research will directly increase the knowledge we have around a relatively new topic in science: microplastics. In particular, I will try to answer a specific question: Do the surface properties that enhance bacterial attachment to chitin also enhance attachment to ordinary plastics surface and, if they do, is there a preference for a specific kind of material? More about Maria’s thoughts on why this matters here!

16. How did you imagine the life of a scientist / researcher when you were a high school student?

When I was in high school, I associated scientists with the typical weird, boring, book-nerdy, geeky and anxious stereotype, kind of like the character Sheldon from the TV series The Big Bang Theory. Therefore, I guess I used to imagine scientists all day long working in the laboratory without a normal social life.

17. Is it actually different? In what way?

To be 100% honest …my idea was not so different from reality! Not literally, of course, but it is true that we spend a lot of time thinking about our experiments, even during weekends, while drinking a beer at a pub, or on birthday parties! At least in my case, my brain doesn’t stop thinking about my research when I get out of the lab, and that sometimes might be perceived by my friends as if I were a bit like Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory. However, I think I can safely say I have a normal social life ;-).

18. What do you like most about the “lifestyle” of a scientist? And what least of it?

What I like about being a scientist …there is no routine working in a laboratory! There is always a new experiment to carry out or something new to learn. What I definitely dislike about the “lifestyle” of a scientist is being a “slave” to the experiments. Some of them are long and require a great deal of attention, which leads to very long hours (including weekends if your experiment lasts more than a week!) in the lab making sure nothing goes wrong. Of course, when the outcomes are aligned with your expectations, or when you find a new and intriguing result, it is very rewarding. However, if results are worthless after having dedicated so much time to an experiment, it is seriously frustrating.

19. Do you think your career would have evolved differently if you were a man?

So far, I don’t think so… I get that in other fields women are a minority and therefore females might experience discrimination, but in Argentina most scientists in my field are women. On top of that, I still don’t have children, so my career has not been affected by maternity leave. Furthermore, I’ve never felt a difference in the progress of my academic career when compared to men.

20. If you were the research minister of Germany, what would you do to improve the situation of women in science?

I had the opportunity to go to the Woman in Science conference in Münster last month and I listened to talks about the situation of women in science in Germany. I think that a lot of progress is being made, e.g. the number of female researchers holding positions as professors has been increasing in the last few years.

On the other hand, for example, being a mother sets up specific challenges to maintaining an academic career. So, I believe that making safe and welcoming workplaces to promote inclusion of academic mums is one of the important items to improve the quality of female life in scientific fields. Regarding that, If I were the research minister of Germany, I would like to raise the support for mums’ attendances at conferences, and to create a baby-change facility and kindergartens in all research institutions with flexible hours.

21. If you had a daughter, what would you advise her not to do?

If I had a daughter, I would encourage her to stay firm with her life choices, and pursue her own dreams. Society is changing and, even when they are not a majority, there are still plenty of men who believe that a woman must be a housewife; I would advise her about that risk and let her know she can do whatever she wants with her own life.

22. What is the biggest challenge for you when it comes to balancing family and career?

I’m the first researcher in my family, and sometimes they don’t understand the implications of pursuing a career in science. For example, it is hard to explain that sometimes I don’t have time to have dinner with them because I have to stay in the laboratory monitoring an experiment. This is especially hard when it happens on weekends.

23. How often do you as a friend / partner / mother / daughter feel guilty when you have to meet a deadline again?

All the time! I feel anxious and stressed near deadlines and I know I can be difficult to be around then. I usually feel guilty after the deadline passes; before the deadline I have no space in my brain to think about that ;-).

24. How did you imagine your future as a child? What profession did you want to pursue?

My dream as a child was to become a park ranger. I love nature and being outdoors; it seemed like the perfect job. However, I finally gave up with this idea because it required me to live far away from my family, and, weighing in all the factors, I’d rather be close to my loved ones.

25. How do you keep your head clear when you are stressed?

Watching sitcoms on Netflix helps me a lot to clear out my mind. I also found that running and making pottery are very relaxing and therapeutic activities.

26. What is your favorite German word?

Glühwein! I tried this beverage for the first time in my life on the Christmas Markets in Münster and I loved it ever since.

27. What makes you most happy about the world?

Playing with my little nephews and niece. Traveling, especially when I get to see the beauty of nature, such as an amazing view of a lake or a mountain (e.g. in Patagonia, which I call “my place in the world”).

28. What or who inspired you to become a chemist?

When I was in high school and I took my first steps in chemistry, I felt a profound feeling of satisfaction when I was able to solve chemical problems in a domain that, until then, was completely unknown for me. I guess I can say that was my first close encounter with chemistry, something like being able to communicate with extraterrestrial life – like chemistry, a strange and completely unknown subject to me.

29. Which of your traits bothers you the most in your daily work?

Tough question … I think that one of the traits that bothers me the most is that I am not a chatty-person, and sometimes that could be perceived by others as lack of interest in them or their own work. The easy answer is that I am not good at doing quick calculations in my head, which forces me to use the calculator more than I would like to ;-).

30. What worries you most about the world?

I tend to believe that we are growing and becoming better as a society. However, I would say that there is still a long road to go regarding world hunger, lack of access to drinking water, and increasing unequal richness distribution.

In my field in particular, I’m worried about the development of “Superbugs”, i.e., bacteria that are resistant to the majority of the commonly used antibiotics, climate change, and, of course, environmental contamination.

31. If you could travel in time: in which epoch and at which discovery or event would you have liked to have been there?

I would like to have been present at The Solvay Conference of 1927, where the world’s most notable physicists (not only from that time, but perhaps from all history of science!) met to discuss the recently formulated theory of quantum mechanics. Almost all the important scientist I learned about during my career took part in that conference: Niels Bohr, Max Born, Paul-Maurice Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Max Planck, Louis de Broglie, Irving Langmuir, Albert Einstein, and just one woman: Marie Curie.

32. What is your favorite place in Münster?

One of my favorite places in Münster is Lake Aasee. It is nice to walk around this place and enjoy the view. Recently, my husband and I started jogging again, and we always go to the Lake.

33. What has surprised you most about the University of Münster?

How well organized the research institutes are and how well communicated they are with other universities in Germany and in the rest of the world.