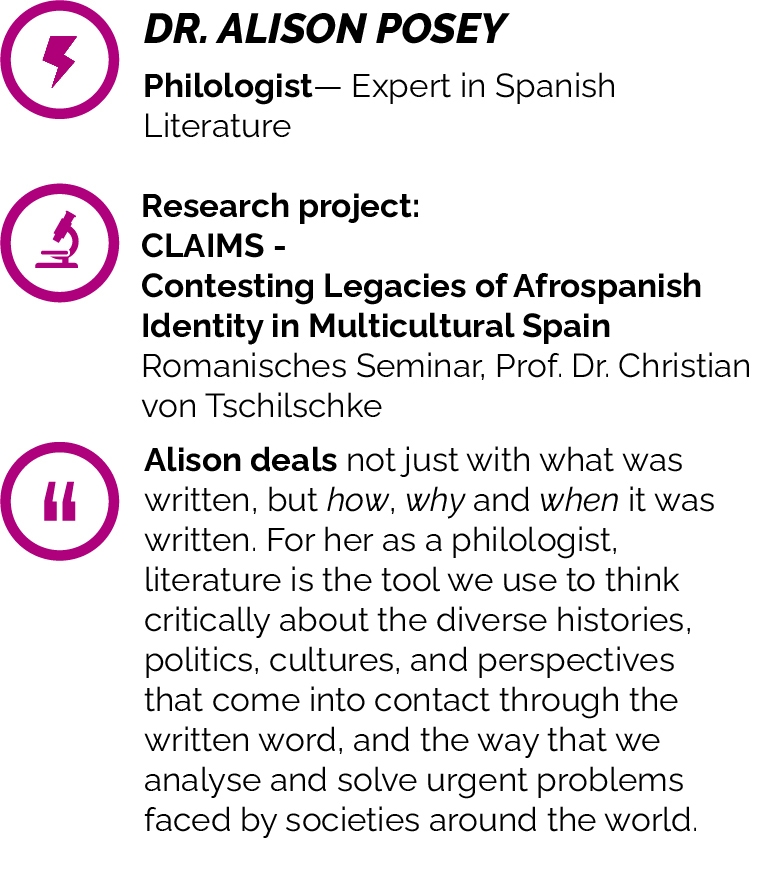

Solving the Pressing Problems of Our Times through Literature: an Interview with Philologist Dr. Alison Posey

In the series “33 questions” we introduce, in no particular order, our WiRe Fellows who are currently working on a research project here at the University of Münster. Why 33? Well, if we think of the rush hour of life, it is kind of the age that lies in the middle. And we also like the number😉.

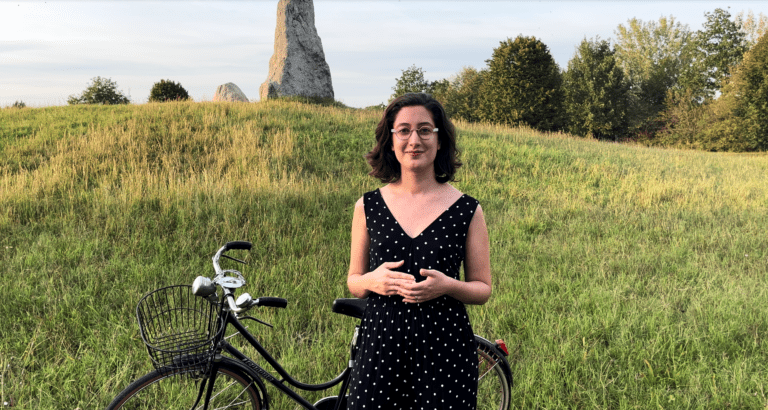

In today’s episode we are speaking with Dr. Alison Posey, philologist and passionate lover of literarture.

1. What motivated you to work in the field of contemporary Peninsular literary studies?

That’s something I am asked a lot – many people find it strange that I devoted myself to this topic, especially since I don’t have any familial or historical connections to Spain. In fact, no one else in my family speaks any Spanish.

I started studying Spanish my first year of university in order to fulfill a graduation requirement. I quickly fell in love with the language, and I was able to study abroad in Ecuador, Perú, and Spain. Studying abroad was what motivated me to change my field of study from English literature to Spanish literature, combining my passion for philology with the desire to challenge myself by becoming fluent in not only another language, but the literatures, cultures, histories, and politics of the Hispanic world. What I love about my field is that it is impossible to be bored.

2. Describe your daily work in three words.

Literature, testimony, identity.

3. Describe your research topic in three words.

Contemporary, autobiography, Spain.

4. A good philologist needs…?

…Critical thinking, patience, and excellent editorial skills. There’s nothing worse than waiting months—or sometimes years—for your article to be published in a journal, and realizing you’ve misspelled something on page 2. It happens more than you’d think.

5. What does a typical (work) day look like for you?

What I love about my job is that no two days are the same! Between long hours spent reading, writing, and teaching, I find that collaboration and conversation with those outside my discipline really inspires me – meaning that I always push myself to make connections with scholars in different fields. While in Münster, I attended a talk here in the University of Münster’s Romanisches Seminar by a Spanish-American scholar and author, and last week I attended a gallery event on AI Art at the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur.

6. What was your biggest research disaster? What did you learn out of it?

I have so many half-written drafts of articles and chapters that I have just… abandoned. They bring to mind the sunk-cost fallacy – the idea that after you’ve invested (time, resources, energy, or even research funding), you have to see a project through regardless of outcome. With this mindset, cutting your losses feels like an admission of failure, but it has helped me see that not every single idea or draft is worth the effort.

Another memorable one is when I misspelled a key term dozens of times in the final draft of a published article. Neither the editors nor I caught the mistake – it wasn’t until a sharp-sighted friend pointed it out that I was able to make the last-minute change. Even the most careful writers and editors mess up.

7. What keeps you motivated in your work day in and day out?

Just like in the United States and the broader EU, Spain is grappling with a dramatic rise of far-right political extremism, populism, and xenophobia in its democracy. Working on authors who openly condemn the violence generated by these kinds of ideologies is essential.

8. Which (historical) important scientist / researcher would you like to have dinner with? What would you ask?

The 17th century self-taught poet, author, and feminist Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. How did she find the courage to confront the omnipresent misogyny of her time, even when it meant risking everything?

9. What or who inspired you to become a philologist?

My mom – I was so lucky to grow up with a passionate reader who filled our home with all kinds of books and never said no to a trip to the library.

10. If time and money were no object: Which research project would you like to do?

I would love to translate the authors I study into English. There are significant parallels between their work and that of contemporary American scholars like Ibram X. Kendi, Clint Smith, and Claudia Rankine, but the authors I study are little-known outside of Spain (though I’m hoping to change that).

11. Which hobby have you given up for a life in academia?

Does free time count?

12. What do you consider the greatest achievement in your field?

I have enormous respect and admiration for Claudia Rankine, the poet-scholar. Her recent work Just Us combines memoir, lyric poetry, and intensive research. It is a text of immense power for anyone working on questions of nationalism, identity, or race today.

13. Which experience in the world of science disappointed you most?

Deciding to do a doctorate in Spanish literature, even pre-pandemic, felt like a risky decision. Since 2015, when I began, and on into today, the humanities have reportedly been on the verge of total collapse; competition is at an all-time high, as more and more highly-trained PhDs compete for less resources and fewer tenured positions in the face of growing hostility to the arts. It’s a disheartening reality, although it reminds me of a quote by environmental educator David Sobel: “Let children be allowed to love the Earth before we ask them to save it”.

I think the same principle applies to the humanities – we need to show others how to value non-STEM fields before we ask them to save them.

14. How did you survive your PhD time, and what advice and tips do you have for future PhD students?

Lots and lots of tea.

It’s an excellent idea to reach out to other scholars in your field. Even if you’ve never met them, there’s nothing wrong with a short, friendly email about a mutual research interest. Developing these kinds of informal networks is so important for your career – it’s what brought me to WIRE and the University of Münster!

15. What direct or indirect relevance does your research have for society?

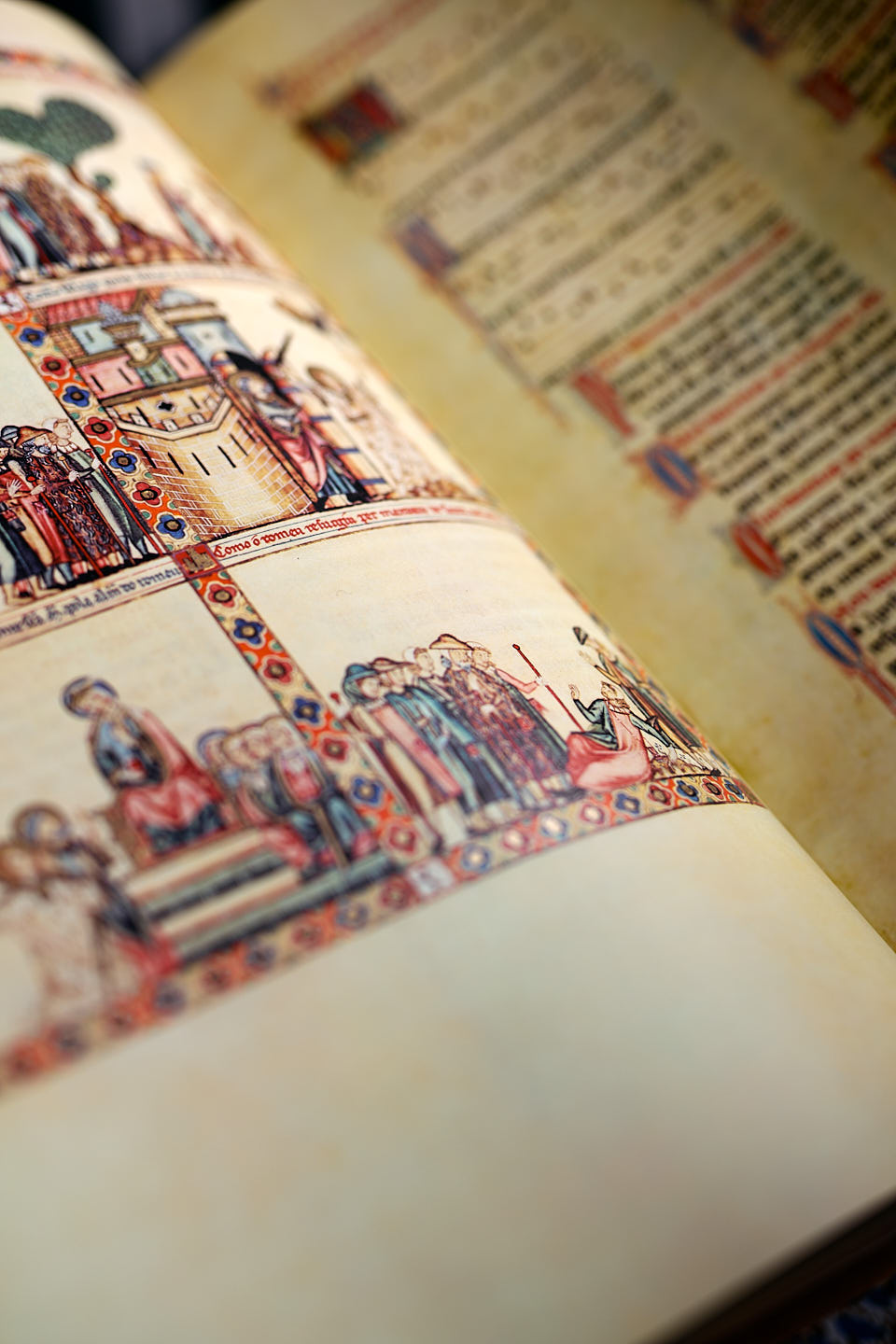

The late-twentieth-century growth in immigration from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia to Spain has intensified debates on who should be included in discourses of national identity. In response to their exclusion from contemporary representations of the nation, a group of dynamic, young Spaniards of color have created a body of literary and artistic production that draws attention to the limits of belonging in culture that perpetuates racialization, marginalization, and exoticization. Recent publications by this group, to whom I ascribe the label of activist authors, represent one of the strongest recent challenges towards traditional notions of national racial identity as fundamentally white. What can Spain’s ongoing struggle with diversification tell us about the power of literature to challenge established beliefs about national identity in Europe today?

By examining testimonies by contemporary authors of color in Spain, my research emphasizes autobiography as a tool to address the urgent issues of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination entrenched in contemporary Western visions of national identity and belonging. In examining the intersection of testimony and activism in Spanish letters, testimonial writing brings to light groundbreaking new visions of representation, community, and belonging in today’s rapidly diversifying Europe. Above all, these activist authors’ testimonies ask us to confront the role that white supremacy historically has and continues to play in (un)making national identity across Europe and the Global North today.

16. How did you imagine the life of a scientist / researcher when you were a high school student? Is it actually different? In what way?

I assumed that anyone who was a scientist spent their days digging up dinosaur bones. So far, no one has asked me to yet, but there’s still time.

Yes – I didn’t meet anyone who was a philologist until I was a university student. I would say the aspect of philology least understood by those outside of the field is the amount of critical and analytical thinking that goes into every article, monograph, or conference presentation. It’s not just simply reading a novel and explaining the plot or the author’s main ideas. Rather, it’s an opportunity to use literature as a tool to think critically about the challenges we face in the world.

17. What do you like most about the “lifestyle” of a scientist / researcher? And what least of it?

I am so grateful for a career that permits me to travel abroad and immerse myself in other languages and literary traditions, which is essential to my research.

While receiving grants to participate in programs like WIRE is what makes my career so exciting, living off of them is not a recipe for financial stability; economic precarity is a burden for anyone considering this kind of life.

18. Do you think your career would have evolved differently if you were a man?

Absolutely. As recently as 2020, one of the United States’ most prestigious Ivy League universities agreed to pay more than one million USD to rectify significant pay disparities between its male and female professors. It is disheartening to see how blatant bias against female academics persists even at the most elite institutions.

19. Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

Ideally, as a tenured professor at an institution that fully supports my work.

20. If you could travel in time: in which epoch and at which discovery or event would you have liked to have been there?

I’m reading Angela Saini’s excellent history of patriarchy, The Patriarchs, in which she discusses early matriarchal societies around the globe. I’d love to experience life in any of the communities she describes!

21. If you had a daughter, what would you advise her not to do?

Not to expect success the first time around. Academia isn’t a career where failure is celebrated, or often even acknowledged. But I think that recognizing the many rejections researchers face throughout their career (or even while just trying to get an article published in a journal) as normal is essential to stave off feeling like a failure.

22. What was the funniest moment you had in research?

Mistranslations and misunderstandings are common when you’re working across multiple languages and regions of the world. In Spain, it’s common to say coger el bus (to catch the bus), but in parts of the Americas, that phrase has a very different meaning!

23. How did you imagine your future as a child? What profession did you want to pursue?

I’ve always been passionate about literature, and I always thought I would be an author. Although my writing isn’t quite the same as the fantasy novels I devoured as a kid, I feel extremely privileged to work in a field that excites me.

24. How would you explain your research area and topic to a child?

Have you heard that saying, “Don’t judge a book by its cover?” Do you ever feel like that is true for people, too? For example, you might see a tall person and think that they must play basketball, but maybe they don’t like basketball, or they don’t play any sports at all. We also know that anyone can play basketball – you don’t have be tall to play.

If we say all tall people play basketball, that’s an example of a stereotype, an assumption about a person or a group of people. Stereotypes aren’t true, but they can be hurtful. For example, a tall person can play any kind of sport they like, or maybe no sports at all. Stereotypes exist about all sorts of things, including about people and skin colors. Can you think of stereotype about somebody? Is it true? Why not? How do you think that stereotype might make that person feel?

I study stereotypes in a country called Spain, which is home to lots of different kinds of people, languages, and cultures. In Spain, a group of Black writers are telling stories about their own lives. They tell these stories in books called autobiographies, which is a kind of story you write about yourself, your memories, and your experiences. They are writing autobiographies to show us that they face a lot of stereotypes because of their skin color. We know judging someone based on stereotypes—or judging book by its cover—is wrong and hurtful. In their autobiographies, these Black writers are showing us that we need to treat all people with respect and kindness, because stereotypes lead us to treat people badly.

25. What is the biggest challenge for you when it comes to balancing family and career? How do you master this / these challenge(s)?

It’s really hard to be present for your loved ones when your day doesn’t follow a neat 9-5 schedule. After teaching and meeting with students during the workday, I often will work late into the night on research– it feels like there aren’t enough hours in the day.

I try to set clear boundaries for my time: not sending emails after 5 or 6pm, for example, although since I work with colleagues across different time zones, this is more of an aspiration than a reality. Finding time for myself and my loved ones, especially while balancing a full-time teaching and research role, is a challenge.

25. How often do you as a friend / partner / mother / daughter feel guilty when you have to meet a deadline – again?

It’s difficult. I think that the emotional labor that women are expected to perform in both our personal, familial, and working relationships, on top of everything else in our careers, often leads us to abandon academia.

26. If you were the research minister of Germany, what would you do to improve the situation of women in science?

I would raise salaries, provide tax relief to young workers struggling financially, and build more affordable and higher-quality housing for visiting researchers and their families. Likewise, visa bureaucracy is a huge roadblock for those wanting to settle permanently in Germany.

27. How do you keep your head clear when you are stressed?

Exercise.

28. What worries you most about the world? And what makes you most happy?

The threat of far-right extremism to democracy worries me, certainly. But I feel hopeful when I speak to young people, it’s wonderful to spend time at the MENSA cafeteria here – I feel really inspired by the students I meet there, who are so excited to tell me about the research they’re passionate about.

29. Which of your traits bothers you the most in your daily work?

Perfectionism. Also, I overuse hyphens in my writing – it’s a bad habit.

30. And which of your traits help you the most in your daily work?

Adaptability.

31. What is your favorite place to relax from research?

Back in Los Angeles, it’s out hiking in the Santa Monica Mountains. Here in Münster, I love to visit the Botanical Gardens at the Schloss. The flower stands at the weekly market are also nice.

32. What is the biggest difference between the academic system you have last done research in and the academic system as you experience it in Münster / Germany?

Compared to the US system, it’s very hands-off.

33. If you could change one thing about the academic system in which you have last done research in, what would it be?

There’s an aggressive push against research in identity, advocacy, race, and even critical thinking going on in the US right now – it’s alarming from both an academic perspective and a moral one.