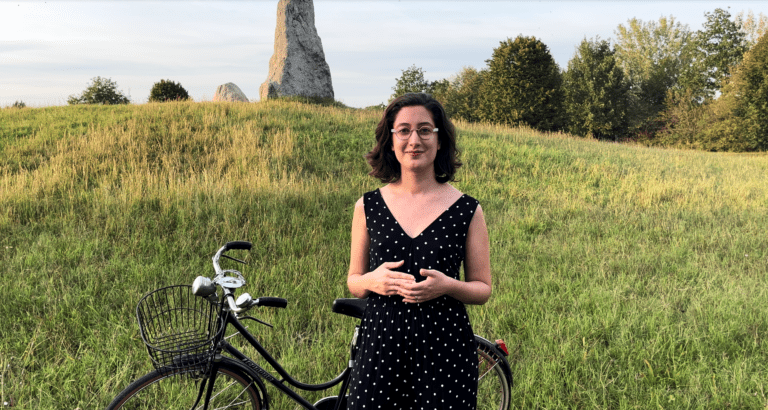

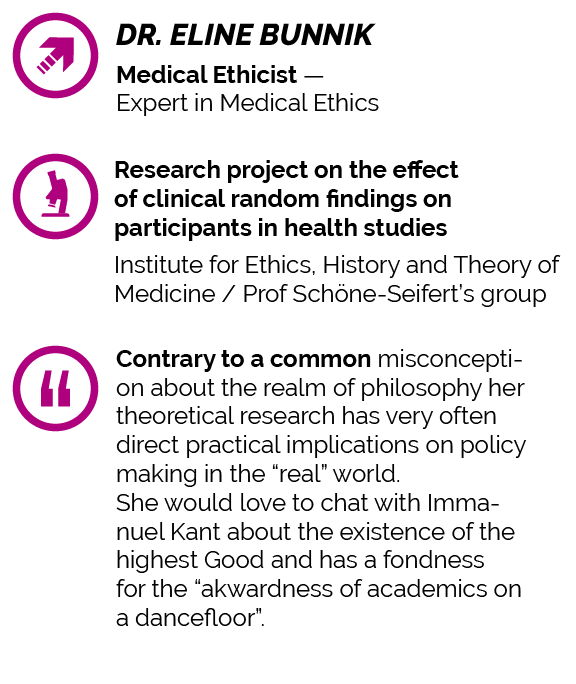

An Interview with WiRe Fellow and Medical Ethicist Dr. Eline Bunnik: Mother, Researcher, Mindfulness Expert

In the series “33 questions” we introduce, in no particular order, our WiRe Fellows who are currently working on a research project here at the University of Münster. Why 33? Well, if we think of the rush hour of life, it is kind of the age that lies in its middle. And we also like the number😉.

In this episode we are speaking with Dr. Eline M. Bunnik, medical ethicist dedicated to analysing and improving ethical aspects of medical research and treatment that affect patients, doctors, and society.

1. What motivated you to work in the field of medical ethics?

I tend to take very theoretical interest in practical issues, I am fascinated by medicine and healthcare, and I enjoy finding ways to make things work in fair ways. In medicine, many things are happening that are affecting patients, professionals and society at large, at a rapid pace, such that we sometimes don’t know what to believe or what to do. I am always attracted to the difficult questions.

2. Describe your daily work in three words.

Thinking, reading, and writing.

3. Describe your research topic in three words.

Ethics of handling incidental findings.

4. A good medical ethicist needs…?

Good relations with people within the hospital and across the country, some basic knowledge about many things within healthcare and medical research, time to focus, and ideally, clever research assistants.

5. What is the best experience you have had as a researcher?

I love doing empirical work. Once, for a research project, my colleague and I went to interview medical doctors in Turkey and in New York. We would ask them difficult questions: “What do you do when you run out of standard treatment options for your patients?”

We took taxis from one New York university hospital to the next and spoke to leading super-specialists with seemingly godlike qualities.

6. What was your biggest research disaster?

My colleagues and I never managed to write a paper on (what I consider to be very valuable) interview data from a project on incidental findings that I was involved in a couple of years ago, out of lack of time and manpower. Luckily, I was awarded the WiRe-fellowship, which now enables me to take on that work again, so hopefully I can make it right.

7. Which (historical) important scientist would you like to have dinner with? What would you ask?

Immanuel Kant. People say he was a rather dull person, who would take identical strolls every day around Königsberg. But I don’t believe this for a second. I can imagine Kant and I would be talking late at night with the light of candles or a fire place. We would have so many things to talk about! I would question him about the Critique of Practical Reason, and the existence of the highest Good, God and the immortality of the soul. There he has never really convinced me – yet.

8. If time and money were no object: which research project would you like to do?

I am very interested in ethical issues surrounding the rising costs of healthcare, especially those of newly approved medical treatments. A lot of interesting questions are arising in this area, related to liberty and autonomy, beneficence, justice and solidarity.

9. What is your favorite research discipline other than your own?

I have always had ‘physics envy’. A friend of mine has written a PhD-thesis that barely contains any words, only numbers. Imagine how different his outlook on life must be.

10. What do you consider the greatest achievement in the history of science / your field?

Medical ethics is a relatively young field. Its greatest task has been to strengthen the position of patients and research participants, especially at times in which they are ill and most vulnerable, vis-à-vis doctors who have always known more and who used to have paternalistic attitudes. Today, patients have the right to receive information, the right to refuse tests or treatments, and the right to decide about their own bodies.

11. Which experience in the world of science disappointed you most?

Science is much more competitive than I thought it would be. The Chair of our department said to me recently that science is like top sports, professional sports, and this struck me as true. This was new to me. Also, there is little glamour in science. What I love about science, though, is that most of us are intrinsically driven.

12. What was the funniest moment you had in science?

I remember this party at the end of an international genetics company and people started to dance. The awkwardness of academics on a dance floor, I find very funny.

13. How did you survive your PhD time?

I had two of my three children during my PhD time. Luckily pregnancy did not negatively affect my brain. I actually had a rather productive, and very lovely time. When I started as a PhD-student, I was highly motivated. Of course I had my moments of (self-)doubt and difficulty, but the writing got easier again after some time, and I started to see the light on the other end of the tunnel. My husband has also earned a PhD at a London university. He says it is an exercise in humiliation. I agree, but you come out stronger.

14. What direct or indirect relevance does your research have for society?

Sometimes, my work has direct relevance for society, when it directly contributes to policy-making. For instance, my PhD-student works on non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). We have been writing a paper that argues that pregnant women and their partners should not be asked to pay out of pocket for NIPT – in a country like the Netherlands, in which all antenatal care, including the 20-week ultrasound, is covered by basic health insurance at the point of delivery. We presented this work to a group of delegates of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, who came looking for input for new reimbursement policies for NIPT. We’ll have to see, though, whether our research ends up in new funding arrangements.

Another example is that as member of the research ethics review committee at Erasmus MC, I help evaluate research protocols, and thus decide whether or not research studies take place at our hospital. Also, I sit on national committees or working groups of physicians’ organizations, helping to develop guidelines or guidance for medical practice. Indirectly, my research contributes to a body of literature that may be used by people – other researchers, health professionals, policy-makers, patients – around the world, who are struggling with theoretical or practical problems and may be seeking ideas or guidance.

15. How did you imagine the life of a scientist / researcher when you were a high school student?

I would not have guessed that I was going to be a researcher when I was in high school. I guess I imagined researchers to wear white coats and spend days in laboratories. I was drawn to philosophy, but I did not think studying philosophy would lead to becoming a researcher.

16. Is it actually different? In what way?

It is different in many ways. I have become a scholar. I spend my days behind my laptop, in meetings, with people in many different constellations, speaking before a range of different audiences, in trains, on airports. I have not discovered anything. But the work is creative, and it’s much more applicable and useful than I would have thought.

17. What do you like most about the “lifestyle” of a scientist? And what least of it?

The freedom, the autonomy, the focus not on form but on content. What I miss about the ‘lifestyle’ of scientists: there are few festivities, there is not much ‘fun’. Things tend to be a little serious. Some of my friends have jobs in entirely different fields, such as education or the arts, and are taken on weekends with their teams to develop theatre shows or throw visually attractive parties for colleagues’ birthdays or farewells with brilliantly conceived performances and presents.

18. Do you think your career would have evolved differently if you were a man?

Yes. I would have been much more productive. A lot of my productivity goes into my children. Also, I would probably have earned more money. Men tend to go and ask for more money, whereas I never have. I do not regret these things, however.

17. If you were the research minister of Germany, what would you do to improve the situation of women in science?

I understand that Germany allows women to take a – partly paid – pregnancy and maternity leave for about a year, and that it offers subsidized childcare for children over 12 months until they go to school. In the Netherlands, women get 3 months leave, and childcare is madly expensive. Germany is doing much better than the Netherlands, but for mothers, not necessarily for women in science. Science is becoming increasingly competitive. This, to me, seems an intractable problem for both men and women. However, at my university, I was selected for a Female Career Development programme that offers a small group of female assistant professors and young medical staff a course-trajectory to help them develop what they call ‘leadership skills’ and further their careers. This initiative is largely state-funded, and aims to increase the number of women at the top in academia. The Netherlands is performing badly, with fewer than 20% of professors being female. These initiatives do help.

18. If you had a daughter, what would you advise her not to do?

I have a daughter, and I will advise her to not study philosophy, like me, or at least not only philosophy, but to pursue a professional education, too. My oldest son has a knack for mathematics, which we encourage. My daughter is a very talented 12-year-old with a strong intuition; she will find her way.

19. What is the biggest challenge for you when it comes to balancing family and career?

Travelling between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. I work hard and I want to spend time with my children. I often dream about missing trains. When working in international research collaborations, it is accepted practice to use Skype or any other medium to convene. It would greatly improve my life if my national or local research groups would wish to meet in this way, sometimes, too.

20. How often do you as a friend / partner / mother / daughter feel guilty when you have to meet a deadline again?

Often. Don’t we all? I wish I had precisely the amount of work to do that would fit in the time that I have in reality and/or the time that is mentioned in my contract. Instead, I always have way too much work to do.

21. How did you imagine your future as a child? What profession did you want to pursue?

I thought I would dance the mambo; I had high expectations. I always said I would become either a doctor or a writer. I have become a bit of both.

22. How do you keep your head clear when you are stressed?

I have the lucky capacity to be ‘present’ in any situation. I never had to practice this; I was born mindful. This is also why I am always late. When I am talking to someone, I lose track of everything else, I could stay like that forever… When I am stressed, I can – usually – easily forget about all of my sources of stress, simply by doing something else, like playing football with my children. Play is a good way for me to relax. I must say that I am increasingly suffering from stress as I am attracting more and more responsibilities at work.

23. What is your favorite German word?

Gestaltwechsel. By far. From Ludwig Wittgenstein.

24. What makes you most happy about the world?

Love, especially the love between my husband and I. My three wonderful children. Learning new facts, having new sensations, travelling, walking around, dancing, ice skating, all those things that make me feel how unlikely and incredible it is that we, humans, are alive in this world.

25. What or who inspired you to become a medical ethicist?

Prof. Dr. Inez de Beaufort, my boss. She is sharp and strong-willed, eloquent and elegant. Also, she demonstrates that academic work does affect policy-making, and has an impact on society.

26. Which of your traits bothers you the most in your daily work?

Well, I do not seek communication with others. I am an introvert; I like working alone. I actually forget about involving others. I know this is one of my weaknesses, I actively try to counteract this, I tell myself to contact others.

27. What worries you most about the world?

There are many things to worry about. The state of the planet, the number of people, the state of democracies around the world, and even more so, of non-democracies around the world. I have the impression that the human world has been expanding for centuries, but is currently prodding against its limits. I am not confident that we, humans, have the wisdom to solve the problems that are confronting us. Still, I tend not to worry.

28. Your favourite TV series?

Homeland. I love Claire Danes.

29. If someone asks you about your age, what do you respond spontaneously?

I usually don’t immediately know the answer to that question. I must always think and sometimes even calculate my age. The number of my age is not so prominent in my mind. I do wish I could be 21 forever, or maybe 27. Instead, I am 36. I regret losing youth, but I like growing older. Youth is wasted on the young, is what Oscar Wilde said. I would be having so much fun if I were 27 now.

30. Which hobby have you given up for a life in academia?

Maybe speed. Getting things done quickly. The pace of academia is relatively slow. It often takes time to achieve things. Also, dinner parties.

31. If you could travel in time: in which epoch and at which discovery or event would you have liked to have been there?

The epoch of John Snow, a British epidemiologist and anaesthesiologist from the mid 1900s. He lived in London and discovered the source of a cholera outbreak in a well in 1854, at a time in which nobody knew about pathogens. Also, while people have always tried to find ways to alleviate pain and reduce consciousness during surgery, all the way back to Mesopotamia, nothing worked like ether and chloroform, which were not developed for medical use until the time of John Snow. Snow used chloroform on Queen Victoria, during childbirth. She was wildly enthusiastic about it, which helped with its implementation in medical practice. I like the romance of the Victorian epoch. There were many things yet to be discovered.

32. What is your favorite place in Münster?

I love walking around the botanical garden and the wide open spaces of Münster, despite January’s cold. The stillness of the St. Paulus Dom. A colleague at the Institut für Ethik, Geschichte und Theorie der Medizin took me to Hans im Glück for a vegetarian burger, in a fairy tale-like setting. I loved Herr Sonnenschein for coffee and for working.

33. What surprised you most about the University of Münster?

During the first days I took pictures of the name signs with all the titles (Univ. Prof.), and the street signs with parking bans on the Münster campus, signed by ‘Der Rektor’. In the Netherlands we have been losing some of that respect for and those formal attitudes towards hierarchy and positions.