Is Spain a White Country? Rewriting Race, Nation, and Identity in Contemporary Spain

During a September 18, 2022, football match, the Real Madrid forward Vinícius José Paixaõ de Oliveira Junior—a Black Brazilian Spaniard widely recognized as one of the best players in the twenty-first century—endured an onslaught of racist epithets from rival Atlético Madrid fans. Despite swift public condemnation, including by the Spanish Congress of Deputies and President Pedro Sánchez, the harassment of Vini continued at matches in December 2022, February 2023, and May 2023. In January of that same year, an effigy of the renowned athlete was hung from a highway bridge. Spain’s lackluster response to these events received a sharp rebuke from Brazilian president Lula da Silva, catapulting the nation’s struggle to address racism onto the international stage.

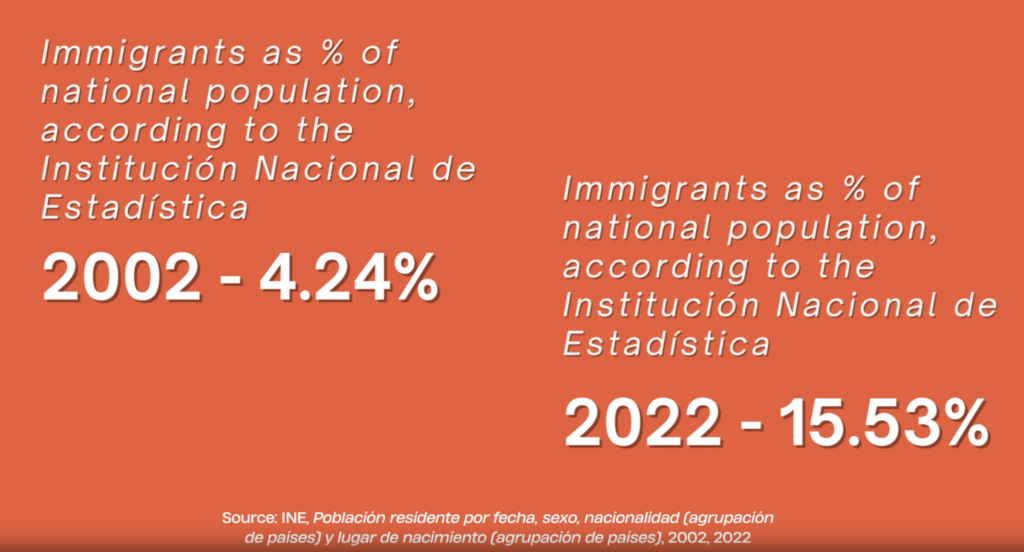

Yet the Vini case is not an isolated one. According to Spain’s Ministry of the Interior, racist and xenophobic hate crimes increased an alarming 31.75% nationwide between 2020 and 2021, vastly outpacing reports in all other categories [1]. Despite Spain’s rich multiracial and multicultural history, the rise of immigration that began in the late 20th century has brought with it the weaponization of Spanish national identity, which emphasizes a false equivalency between whiteness and national belonging. As courts have attempted to bring many perpetrators of the Vini case to justice, the far too common experience of this star footballer reiterates the enduring discrimination citizens of color still face in Spain today.

Contesting Histories, Challenging Identities

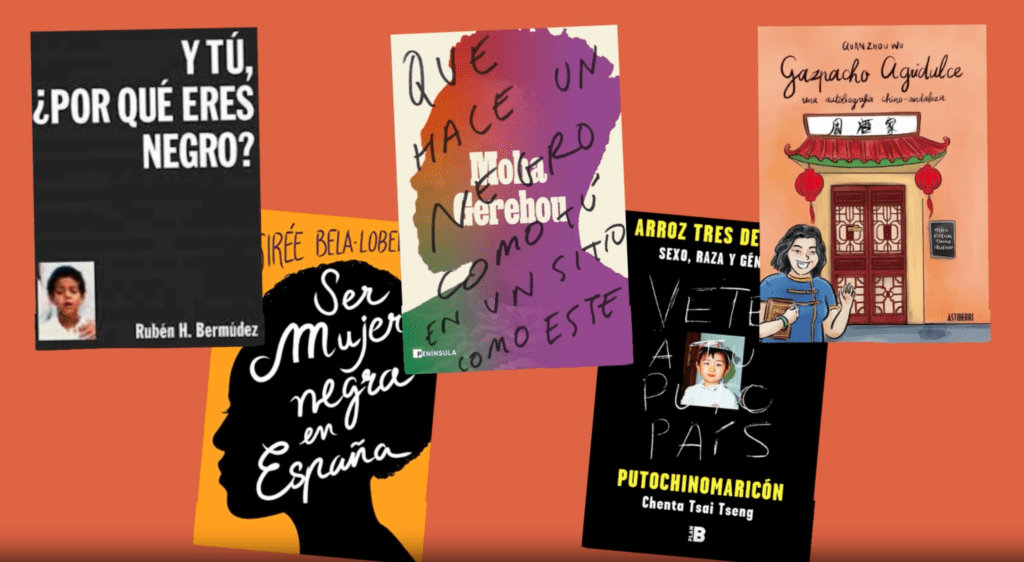

Can writing separate notions of race from notions of national belonging? To answer this crucial question, I investigate a generation of Black authors in Spain today who use self-referential life writing to advocate for a national identity inclusive of racial diversity. Faced by the deeply inequitable reality in which “the rights afforded by citizenship are undermined by the lived experience of being a visible minority, marked as ‘other’ by skin color” (Moji 61) [2], these authors, who include Desirée Bela-Lobedde (1978-), Lucía Mbomío (1981-), and Moha Gerehou (1992-) have penned a slew of self-referential texts that personalize experiences of racism for a largely white, Spanish audience. My research argues that their autobiographic works, which demand that readers witness the racism and xenophobia experienced by the authors themselves, had have a seismic effect on contemporary understandings of national identity in a country that has long denied its multiracial past.

Spain’s extensive historical relationship with the African continent includes the Muslim rule of Iberia (711-1492), after which the victorious Catholic kings instituted policies of forced conversion and exile for those deemed to have “impure” blood; the nation’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, which increased the African population of the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th and 16th centuries while enriching port cities like Sevilla and Cadiz; and its colonialization (in addition to its established, better-known empires across the Americas and Asia) of Morocco, Western Sahara, and Equatorial Guinea, which gave birth to diverse Hispanophone communities and cultures across Northern and Western Africa. Today, Equatorial Guinea is the only African nation that recognizes Spanish as an official language.

As author, educator, and activist Desirée Bela-Lobedde explains in her 2018 autobiography, Ser mujer negra en España [Being a Black Woman in Spain], the true story of Spain is one that affirms the central role its citizens of color have played across its history:

en España ha habido personas negras desde hace siglos. Es que no puede ser de otra manera. ¡Estamos a solo catorce kilómetros de África, por favor!…contémoslo todo y contémoslo bien para que podamos entender que España es el resultado de la mezcla desde hace siglos, no desde hace un par de décadas cuando estalló el ‘Fenómeno Migratorio’. Es necesario ese cambio…Es justo y necesario. (169-70) [3]

[In Spain there have been Black people for centuries. It can’t be any other way. We’re only fourteen kilometers from Africa, for goodness’ sake! Let’s tell it all and let’s tell it well so that we can understand that Spain is the result of a mixture going back centuries, not just going back a few decades when the ‘Migration Phenomenon’ blew up. That change is necessary…It’s right and necessary] [4]

As Bela-Lobedde demonstrates, the recent surge in immigration to democratic Spain does not represent a drastic change to the country’s demographic makeup if viewed through a historic lens that takes into account its complex multiracial and multicultural history. Yet contemporary far-right political parties, appealing to the perennially popular populist trope of natives versus invaders, have increasingly sought to depict Spaniards of color as foreigners, whitewashing the country’s past in order to justify the xenophobia and racism essential to their electoral success.

(Re)writing Spain for a Better Future

In their writing, authors like Bela-Lobedde strategically engage various schools of self-referential life writing, such as autobiography, autofiction, and collective testimony, to contest the long-standing belief that Spain is (only) a white country. In this limited perspective, to be Spanish is to be white; to be anything else is to be from anywhere else. My research finds that life writing is a means by which authors reappropriate experiences of racism into activism and transform their narratives into a crucial act of agency. To define identity as multiple—as Afrospanish, as a Black Spaniard, or as an Afrodiasporic European, for example—is to assert authority over established narratives of false equivalency that unjustly exclude Spaniards of color from inclusion in a national identity that is their birthright. Life writing, as my research has found, thus permits writers like Bela-Lobedde, Mbomío, or Gerehou to politicize the private in order to effect radical change for future generations of Spaniards. In their texts, they (re)present and (re)write national identities that offer alternatives to the present-day binary of white/Spanish versus Black/other, and envision a nation that, critically, celebrates all heritages.

Investigating questions of race, identity, and national belonging are critical to understanding the struggles that democracies worldwide face today, as they seek to address the surges in racism and xenophobia that often accompany ongoing demographic shifts. As the Vini case makes clear, despite Spain’s long history as a multicultural and multiracial nation, racism remains rife as the country grapples with what it really means to be Spanish in the twenty-first century. However, as my research demonstrates, literature is a key method for challenging and critiquing exclusionary notions of national belonging. Reading and writing race in Spain creates bridges across diverse cultures, communities, and countries to offer us paths away from racism and xenophobia towards a better future for all.

Works Cited

[1] Guitérrez et. al. Informe sobre la evolución de delitos de odio en España 2021. Gobierno de España, Ministerio del Interior, Oficina Nacional de Lucha contra los Delitos de Odio, 2021, www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/servicios-al-ciudadano/delitos-de-odio/estadisticas/INFORME-EVOLUCION-DELITOS-DE-ODIO-VDEF.pdf

[2] Moji, Polo B. Gender and the Spatiality of Blackness in Contemporary AfroFrench Narratives. Routledge, 2022, doi.org/10.4324/9781003120544.

[3] Bela-Lobedde, Desirée. Ser mujer negra en España. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial España, 2018.

[4] Translation my own.